Boomtown1

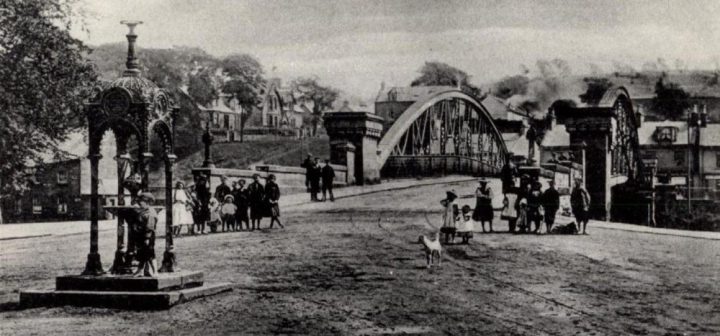

In early 1851, Queen Victoria was getting ready for the opening of the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, which everyone hoped would buoy the spirits of the British people. The previous decade had been hard for everyone in the Isles, but crop failures and potato blight in Ireland and Scotland had been devastating. Yet in the Vale of Leven, between Loch Lomond and the River Clyde, there was hope. The village of Bonhill was flourishing. It had become the Scottish epicentre of the calico printing business due to local expertise with the very tricky process of manufacturing Turkey Red, a bright and coloutfast dye ideally suited for cotton.

Now, don’t get the wrong impression. Life in Bonhill was grim. Even those with jobs were living a life we would consider intolerable. Typically, 2 or 3 generations would share a couple of rooms in a house, which was itself shared among several families. There was no plumbing. Dismal as it was, it was better than the alternatives, particularly Glasgow which was becoming a synonym for urban blight and decay.

A branch of the Brannan family lived in Bonhill. Like thousand of others, they came to find work. But this isn’t a story about the Brannans, at least not yet. This is a story about a bairn or wean from Glasgow.

Let’s start with John Brodley. He married Isabella McCallum on 19 April 1851 and had a daughter, Eliza, a few years later. John’s family was from Dumbarton, but he had moved to Bonhill to work as a calico block printer and to be with Isabella. They lived with her aging father and her son, whose father was long gone. The boy, Archie Campbell, was just 14 but already working in the dye-works. Although money was scarce, they survived by renting out most of the rooms in her father’s house to another family.

As the years passed, John couldn’t say that he was unhappy. He’d spent a decade in the Bonhill printworks and, yes, it was a hard life, the hours long and the pay meager, but it had mostly been steady. He loved Isabella and their daughter was able to attend the factory school. They were getting by.

Introducing the Elizabeths Aimer

In 1861, John got a message from Glasgow. A widow there, Elizabeth Aimer, had a newborn baby, also called Elizabeth, and she said that John needed to come and take care of her. The woman’s husband had died, leaving her to care for their 4 children on her own. It’s not surprising that she couldn’t handle a fifth. So he talked to his wife, who agreed that Glasgow was no place for a child2, and little Elizabeth Aimer started a new life in Bonhill3. At least with the Bradleys she stood a chance of surviving.

Why did the woman from Glasgow get in touch with John, and why did he agree to take the baby into his household? Was he the father? It is impossible to say for sure, but I don’t think so. When the census taker called years later, they said the child was a boarder. Given that Isabella felt no need to disguise the fact that Archibald, was her son, even though she wasn’t married when he was born and the father had abandoned them, it would be strange to hide the identity of John’s daughter, if it were true.

Regardless of the reason for bringing the baby to Bonhill, it seems that little Elizabeth not only survived but spent her childhood as a loved member of the Bradley household. The two other children, Archie and Eliza, both worked in the factories, and Elizabeth Aimer was able to go to the factory school

Unfortunately, it didn’t last; sometime in the 1870s, John and Isabella grew apart. Isabella died in 1880 from “erysipelas and inflammation of the membrane of the brain”. Her marital status was listed as “Single” which clearly means that the marriage to John had ended. We don’t know if they were formally divorced which, at the time, was only possible due to adultery. Eliza (her daughter with John) and Archie (her son with Duncan Campbell) just seem to vanish from the records. John and Elizabeth Aimer were now alone.

Still, John had done what he promised; he had protected Elizabeth Aimer. By her 20th birthday, people had forgotten, or no longer cared about, her birth family and John started telling people that she was his daughter. Whether she had been formally adopted or not, she began calling herself Elizabeth Bradley.

Then Thomas Branan (sic) and his family moved into the same house on Croft Lane where John and Elizabeth were living. Now a young woman, Elizabeth Aimer Bradley’s life was about to change again.

There goes the neighbourhood

This diagram might be helpful to keep track of the various Brannans that play a part in the drama. Too many of whom are Jameses.

Sometime in the 1840s, James and Mary Brannan brought their 3 teenage sons from Dumbarton to work in the Bonhill printfields. Before that, there were no Brannans in the Vale of Leven.4

It was a difficult life. In 1857, James applied to the parish church for welfare due to “cholera”. and it is likely that he died soon thereafter. He was 57. His wife, Mary, survived and lived on her own at times or with her sons. Her last mention in the official records is as an inmate at the Dumbarton Combination Poorhouse in 1881. There, she died a “pauper” on 1 August 1881 due to “apoplexia“.

Only one of their sons remained in Bonhill. His name was Thomas and, in 1856, he married Martha McDougall Galloway5. They had a son, James McDougall, and 2 daughters, Martha and Annie.

All that is preamble to what comes next.

Biology

In 1881, Thomas and Martha Brannan moved into rooms on Croft Lane, along with their two younger children: James MacDougall (19) and Annie (6).

John Bradley and the young woman, Elizabeth Aimer Bradley (20), had rooms in the same house.

It was inevitable that the Brannan boy and the Bradley girl would notice each other. We all know what happens when two hormone addled 20 year olds live together in close proximity. It’s not rocket science.

On 10 August 1882 at 1:30 a.m., in her room at 11 Croft Lane, Elizabeth Aimer Bradley gave birth to a son, James Bradley (illegitimate, per the statutory register). The father was likely in the very next room.

The young couple weren’t married, but lived with both their families, and their child, under one roof. This wasn’t as weird as it sounds. In mid-1800s Scotland, and particularly in the Vale of Leven, people had a lot of pre-marital sex.6 It was not uncommon for a woman to conceive a child, and sometimes give birth, before marrying the father. It has even been said that “Scottish courtship frequently took place after dark, indoors and in bed.”7

This wasn’t because they were overly active fornicators. Rather, it was because divorce was very difficult, so couples wanted to test the relationship before making a hard-to-reverse official commitment. And although we tend to think of the Scottish Presbyterian church as a rigid and strict institution, they tolerated the practice. The Scots religion put a high value on independence and self reliance, so society and the church actually discouraged marriage until the couple achieved a minimal level of financial independence.

These forces resulted in relatively frequent pre-marital conception, with little pressure for forced marriages. As long as the child was cared for, and the church had the legal authority to make sure of this8, then marriage a few years after a child was born was an accepted practice with little stigma.

For James and Elizabeth, the arrangement lasted longer than most. For nearly a decade they maintained the facade that there were two separate households at their home on Croft Lane: the Brannans were in one and the Bradleys were in the other. Officially, that’s how it was.

The charade ended on New Year’s Day 1892, when James and Elizabeth were married. Elizabeth added Brannan to her growing moniker and became Elizabeth Aimer Bradley Brannan. Her son became James Bradley Brannan, under Scots law, no longer illegitimate.

So around the time of her 31st birthday, and against considerable odds, the unwanted baby Elizabeth, from the Gorbals slums in Glasgow, had grown into a wife and a mother. She was also my great-great-grandmother.

Who was Elizabeth Aimer, really?

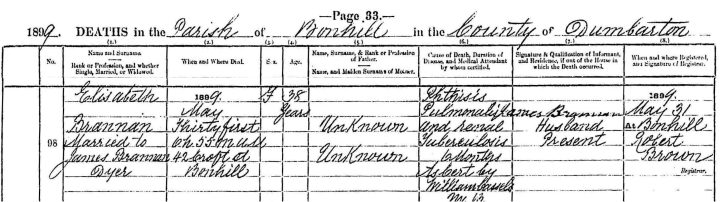

A few years after they were married, James and Elizabeth had another child, Thomas. But then, disaster. At the end of 1898, Elizabeth took sick with phthisis (or tuberculosis) and died on Croft St in Bonhill on 31 May 1899.9

Elizabeth Aimer Bradley Brannan’s death certificate states that both her mother and father were “Unknown”. This supports my theory that John Bradley was not her father and must have had another reason for taking care of Elizabeth. If John had been her biological father, surely she would have told her husband, who would have provided this detail for her death certificate.

We also have the record for John Bradley’s death from hemiplegia on 28 Jan 1892. It was attested by “James Brannan, Acquaintance“. Again, if John was Elizabeth’s father, then the relationship to James Brannan would have been “son-in-law“.

The marriage record for Elizabeth and James is the same. Her parents are both “Unknown“.

No, Elizabeth’s real father must have been someone else. But who?

It is sheer speculation, but I think it was John’s younger brother, James Broadley. The two of them had lived together in Glasgow in the 1840s, before John moved to Bonhill to marry Isabella McCallum. After John left, variations of the name James Broadley starts to show up in Glasgow prison records, and also as a hand on ships docked in Glasgow. Is it the same James? Possibly, although spellings and birthdates vary a bit.

But, it’s not hard to imagine that a near destitute widow in Glasgow might have become pregnant from a relationship with a wayward sailor. And that the widow appealed to the seaman’s brother for assistance. That’s one possibility.

Here’s another.

We know that Elizabeth Aimer Bradley Brannan was born in late 1860 or early 1861, because she was listed on the April 1861 census as being 3 months old. However, there is no record of an Elizabeth Aimer being born in Glasgow, or anywhere else in Scotland, near that time. However, in December 1860, a baby was born in Glasgow to a James and Elizabeth Broadley and the child’s name was Elisabeth10. We don’t know if this James Broadley is related to our John Brodley/Bradley who moved to Bonhill (he was shown as “John Broadley” in the church record of his marriage to Isabella McCallum). But this Glasgow baby’s birth date exactly fits with the age given by Elizabeth Aimer for the baby boarding with her when the census was taken11. Moreover, the father’s last name is pretty much an exact match for the name of the man who came to Glasgow to take responsibility for the baby.

Maybe the widow Aimer isn’t the mother of baby Elizabeth. Maybe the real mother couldn’t care for the infant; maybe she fell sick or died in childbirth. Maybe the father was in jail or at sea. Maybe widow Aimer took over responsibility for the baby, and maybe she was able to locate his brother, and convince him that he needed to help.

That’s a lot of maybes. But it does explain why all the official records for Elizabeth Aimer Bradley Brannan show both her father and mother as being “Unknown“.

Is any of this true? We will never know, but there is one other tidbit that says James Broadley was Elizabeth’s true father.

In 1891, when unmarried Elizabeth Aimer Bradley and James McDougall Brannan and their son were living with their families, it was a census year. The head of the Bradley household that year was reported to be “James Broadley”, and there was no John in the house at the time. Perhaps it was an error by the census taker who wrote “James” instead of “John“, but I prefer to imagine that James Broadley had come as an old man to meet the daughter that he had abandoned in his wild and irresponsible youth.

That part could be true, couldn’t it?

Afterlude

Elizabeth Aimer’s son, James Bradley Brannan was the first Brannan in the Vale who didn’t work in the printing factories. That business was dying12, due to low priced foreign competition, so James became a butcher.

On 20 December 1905, he married Margaret Glen Hudson from the adjacent village of Renton. They had 7 children, 2 of which died in childhood. Their 6th child was a daughter, Margaret Glen Hudson Brannan, and her son William was born in 1934. His birth extended the Brannan tradition of conception of the first child outside of marriage to 4 consecutive generations13. He was my father, and he died in 2024. To the best of my knowledge, my own conception broke the chain.

Here are a couple of pictures. One of William Brannan with his mother, Margaret Glen Hudson Brannan. The other is a very beguiling photo of me, with my great-grandmother, Margaret Glen Hudson.

The history of the Brannans in the Vale of Leven isn’t filled with illustrious and powerful people; quite the opposite. Yet, I think their stories are worth telling and I hope you agree.

I haven’t even begun researching the Hudsons yet. But I understand they were the “respectable” branch of my father’s family so maybe their stories would be boring.

- I had a strong urge to call the section “McBoomtown”, but was able to resist the temptation. I hope you appreciate my restraint ↩︎

- Elizabeth and her husband, George Aimer, lived on Coburg St in the Gorbals section of Glasgow, south of the River Clyde. I’m not sure what life was like when they arrived, but when Elizabeth Aimer was born in 1861, it was probably squalid. Attempts to develop an upscale residential neighbourhood in the early 19th Century had failed and the area became known for overcrowded slum tenements. Life would have been bleak; disease, crime, filth and poverty were rampant. There are some pictures of just how horrible it might have been at this link:

https://flashbak.com/thomas-annans-powerful-photographs-of-the-old-closes-and-streets-of-glasgow-1868-426273/ ↩︎ - It isn’t clear what happened to the widow Aimer after John Brodley took baby Elizabeth to Bonhill. We know that her oldest son, John, was married in 1867 and then moved to Manchester with his younger brother, George, for a while. Perhaps this was because work in the Scottish printworks dwindled in the 1860s when the northern US states’ blockaded cotton exports from the rebellious south. Maybe their mother went with them, continuing to care for her two youngest. Or perhaps she remarried and took another name. Or maybe something else. John, returned to Glasgow, but succumbed to tuberculosis in 1877. His mother was still alive at the time, but had passed away by the time her youngest son James died of liver cancer in 1910. George emigrated to the US, and lived until 1915, when he passed away in Michigan. ↩︎

- The 1841 Scottish census lists 328 people with some variation of the Brannan name, but none of them were in Bonhill or anywhere else in the Vale of Leven. Some of them were in jails, but I wouldn’t know anything about that. ↩︎

- Martha’s story is another sad one. She was destitute with a 5 month-old daughter (Martha) in April 1856 just months before she and Thomas Brannan were wed. Her application for welfare/parochial relief shows her residence as “Wandering”, and she was accused of lying by the church worker. ↩︎

- About 10% of births were outside of marriage with the Vale of Leven being near the high end, and Glasgow a bit lower. (See for example: Annual report of the Registrar General for Scotland. Reports 1-15. Nos. 11-15 include vaccination reports., 1855-1869). For comparison, the illegitimacy rate in England at the time was around 5%. However, if you include pre-marital pregnancies, not just births, the numbers would be in the 20% range for Scotland, but only 10% for England. ↩︎

- Reid, A. and Blaikie, A. (2006). Vulnerability Among Illegitimate Children in Nineteenth Century Scotland. Annales de démographie historique, No 111(1), 89-113. https://doi.org/10.3917/adh.111.0089. ↩︎

- At the time, the church was responsible for providing welfare assistance to the destitute, so they had an interest in encouraging/requiring financial independence. The Kirk Sessions had quasi-judicial authority to force unwed fathers to provide support for their children. ↩︎

- James Macdougall Brannan, on the other hand, lived for many more years. He remarried in 1911, and died of influenza on 18 Jan 1951.His second wife was Susan Cunningham, who he met at 42 Croft St, where he continued to live after Elizabeth Aimer died. They had a daughter, Susan Hay Brannan, who was born the same year they were married. This is a branch of my family that, I have never heard of. Susan Cunningham died in 1969, and their daughter died in 1982. ↩︎

- This James and Elizabeth had 2 children before Elisabeth. The first was a boy, James, who was born in January 1856, but died before his first birthday. The second was a girl, Margaret, born in March 1859, but her fate is unclear. I can’t find her in the 1861 census, nor can I find a record of her death. So, who knows. ↩︎

- The census records the baby’s name as Elizabeth Aimer, not Elizabeth Broadley, but it may have been simpler to give her the same name as the other children, rather than explain her family history. ↩︎

- I’m sorry. ↩︎

- Thomas Brannan + Martha Galloway (m. Sep 1856) ➡ Martha (b. Jan 1856); James Macdougall Brannan + Elizabeth Aimer (m. Aug 1892) ➡ James Bradley Brannan (b. Jan 1882); James Bradley Brannan + Margaret Glen Hudson (m. Dec 1895) ➡ James Brannan (b. Apr 1906); Margaret Glen Hudson Brannan (unm.) ➡ William Brannan (b. 1934). ↩︎